Open-source communities are often seen as paragons of decentralized collaboration. But even in these systems, invisible hierarchies shape how people contribute, coordinate, and influence. Can we better understand these structures—not just who contributes the most, but how participation patterns emerge, persist, and evolve?

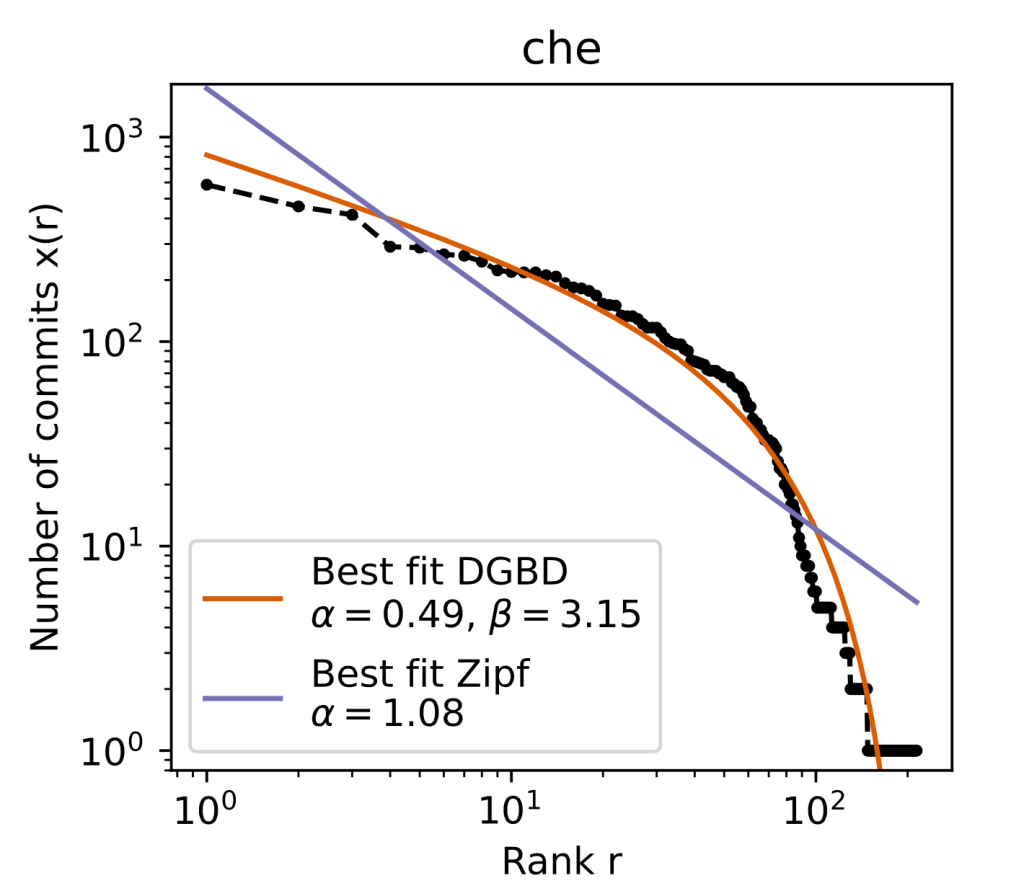

In our recent study published in Physica A, we explore this question using rank-size distributions—mathematical tools that map how activity is distributed across contributors. The most famous of these, Zipf’s Law, has long been used to describe hierarchies in systems as varied as cities, languages, and scientific publishing. It assumes a simple power-law decay: the second most active contributor does half as much as the first, the third one-third, and so on. But while this model is elegant, it’s also limited.

Zipf’s Law tends to focus on the long tail of infrequent participants and often overlooks the middle and upper parts of the distribution—where the most engaged contributors and core teams reside. This blind spot matters, because how participation is structured—not just how much of it occurs—shapes the governance, resilience, and inclusivity of collaborative systems. So, what do rank distributions actually tell us about participation?

In collaborative environments, not everyone contributes equally. Rank distributions capture this inequality by ordering contributors based on their level of activity (e.g., number of commits). The shape of that curve—steep or flat, concave or convex—tells us how centralized or distributed the work is. A steep Zipf-like curve signals a few highly active individuals dominating the system, while a concave distribution implies a more distributed, layered structure, where mid-level contributors play meaningful roles. Understanding these shapes can help us move beyond simplistic metrics like activity counts or averages. They reveal how influence is distributed, whether systems are open to new contributors, and where bottlenecks or burnout might occur.

To go further, we propose the Discrete Generalized Beta Distribution (DGBD) as a more accurate model of participation in open-source repositories. This two-parameter distribution generalizes Zipf’s Law and is better suited for data with concave shapes—a common feature in real-world collaborative platforms like GitHub. Using commit data from hundreds of GitHub repositories, we demonstrate that DGBD consistently outperforms Zipf’s Law, particularly in larger projects (N ≥ 100). It captures the full range of participation—from core contributors to peripheral users—with higher fidelity. We also show that visual inspection and statistical tests alone can be misleading, and emphasize the use of binning techniques (log, mean, and geometric) to avoid overfitting to noisy tails or underweighting the top ranks.

This isn’t just a technical tweak. It has real implications for how we analyze, govern, and design participatory systems. Accurate modeling of rank distributions can help detect emerging power structures or elite dominance, evaluate the health and sustainability of communities, inform platform governance and moderation policies, and support the design of tools that foster more equitable engagement.

In a moment when distributed collaboration is shaping everything from code to science to politics, we need better ways to make sense of the patterns beneath the surface. Rank-size distributions are not just statistical curiosities—they’re lenses onto the deep structure of participation.

📄 Read the full paper: Physica A, 2024

📊 Summary thread: