Over several days, I joined a group of approximately thirty educators, artists, and researchers for the Crafting Pedagogies of Togetherness residency—a prototype initiative investigating how embodied awareness practices can inform both educational pedagogy and collaborative methodologies. The residency was designed and facilitated by Studio Atelierista as part of a project co-funded by Erasmus+, and took place in a rural studio context, functioning as a site of transdisciplinary experimentation. Together, we articulated and tested new forms of learning that are relational, affectively attuned, and somatically grounded.

Rooted in awareness-based embodied practices, the residency invited us to test methods that treat the body as a site of knowledge. Drawing from Social Presencing Theater (SPT) and Awareness-Based Design, we crafted experiences that bypassed purely cognitive modes and instead honored learning as something felt—with and through others.

SPT, developed by Arawana Hayashi and the Presencing Institute, integrates contemplative movement and social inquiry to explore collective presence. Its foundation in Theory U—a framework introduced by Otto Scharmer—, which positions “presencing” as a capacity to perceive and act from emerging future potentials rather than reactive repetition of the past. Within this paradigm, the quality of attention—individual and collective—is understood to have generative, even ontological, implications.

The residency was structured around three core principles: learning to be present with others without a specific goal (Being Together), noticing the emotional and spatial qualities of how we connect (The Aesthetics of Togetherness), and creating meaning and action together from a shared sense of awareness (Relational Creativity).

This work echoes the concept of social somatics, which we explore in a recent article with Boaz Feldman. It focuses on how the felt experience of being in relationship—what it’s like to be together—can inform the design of more connected and responsive educational and organizational settings. It also resonates with insights from contemplative science, which studies how practices like mindfulness and embodied awareness can shape perception, cognition, and social understanding. For researchers in network science, this kind of group interaction can be understood not just as simple links between individuals, but as higher-order connections—like in a hypergraph, where multiple people are part of the same moment or experience. In this view, relationships are not just one-to-one links, but shared events that are co-experienced, co-created, and shaped by attention and presence.

One notable exchange during the residency took place with Amruta Bahulekar, Chief Program Officer of the Lighthouse Project in India—a large-scale intervention reaching over 50,000 youth from urban informal settlements, providing pathways from exclusion to employment and lifelong learning. Together, we examined the methodological challenge of measuring the intangible: how might we rigorously document shifts in self-confidence, trust, or relational well-being? We explored approaches such as narrative-based self-reporting, AI-assisted qualitative analysis of large-scale textual corpora, and art-based sensing practices—including collective drawing as a mode of capturing the experiential field.

This exploration led us to reflect on the different ways of knowing that can be brought into a group process. Rather than privileging a single perspective, we experimented with integrating four complementary vantage points:

- 1st person – the participant’s direct, subjective, and embodied experience;

- 2nd person – a cognitive and empathic stance, speaking from the perspective of another (“you”) to illuminate interpersonal dynamics;

- 3rd person – structured observational or ethnographic accounts from outside the interaction;

- 4th person – a participatory, field-based mode of knowing through aesthetic or intuitive sensing (e.g., drawing what the relational field “says”).

Taken together, these perspectives invite a multi-modal integration of knowledge—subjective, intersubjective, objective, and participatory—that challenges the narrow privileging of detached observation in social research. This approach aligns with emerging views in intersubjectivity and distributed cognition, where knowing is not fixed or singular, but situated, relational, and co-produced.

In practice, one experiment involved adapting the SPT “group of five” format to include verbal self-inquiry, generating first-person experiential accounts in real time. This hybrid form introduced a noticeable shift: while verbalization brought attention back to individual identity and narrative, it also sharpened group-wide perception and resonance. We found that such interventions require time and scaffolding but open rich ground for shared reflection.

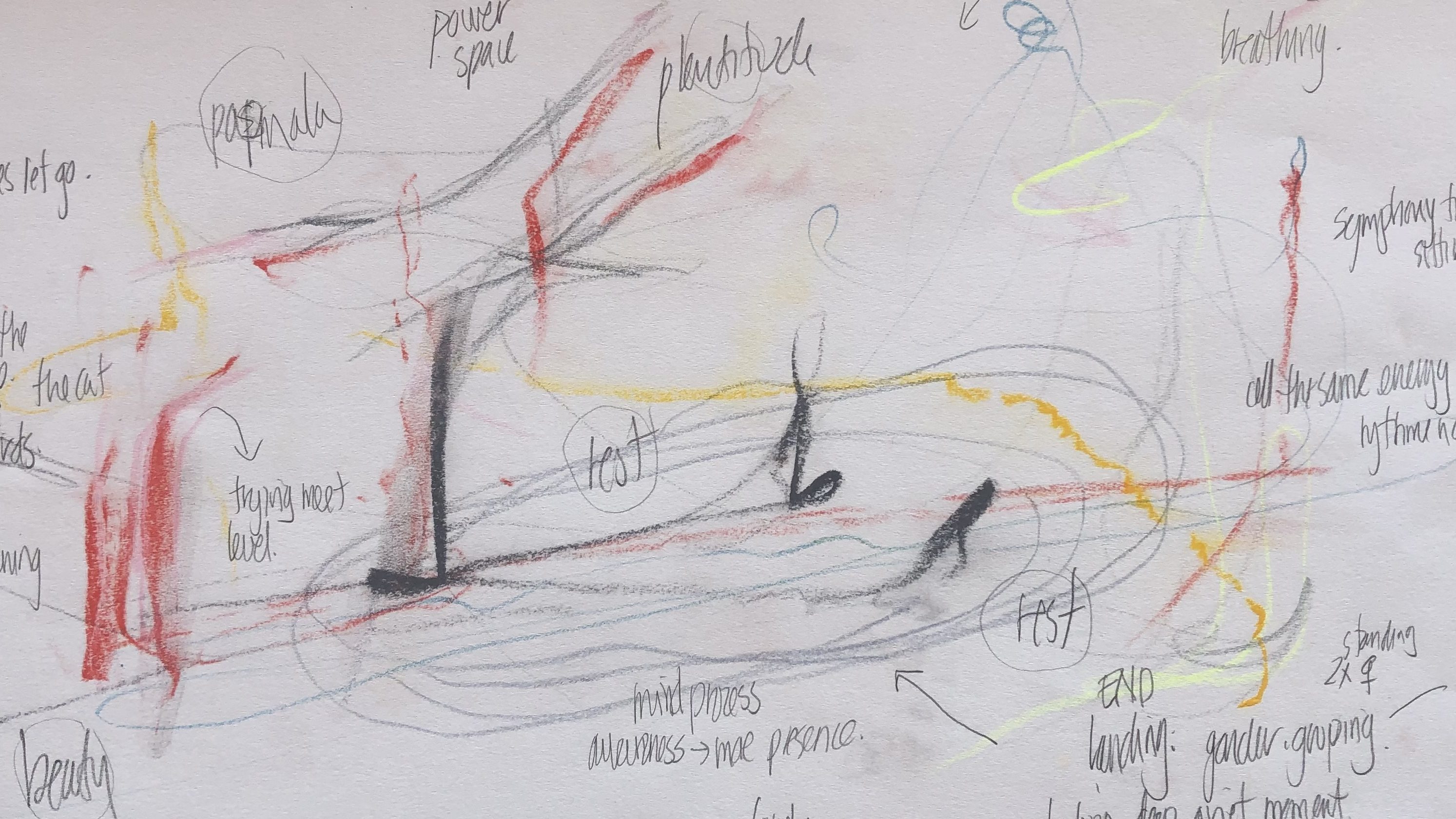

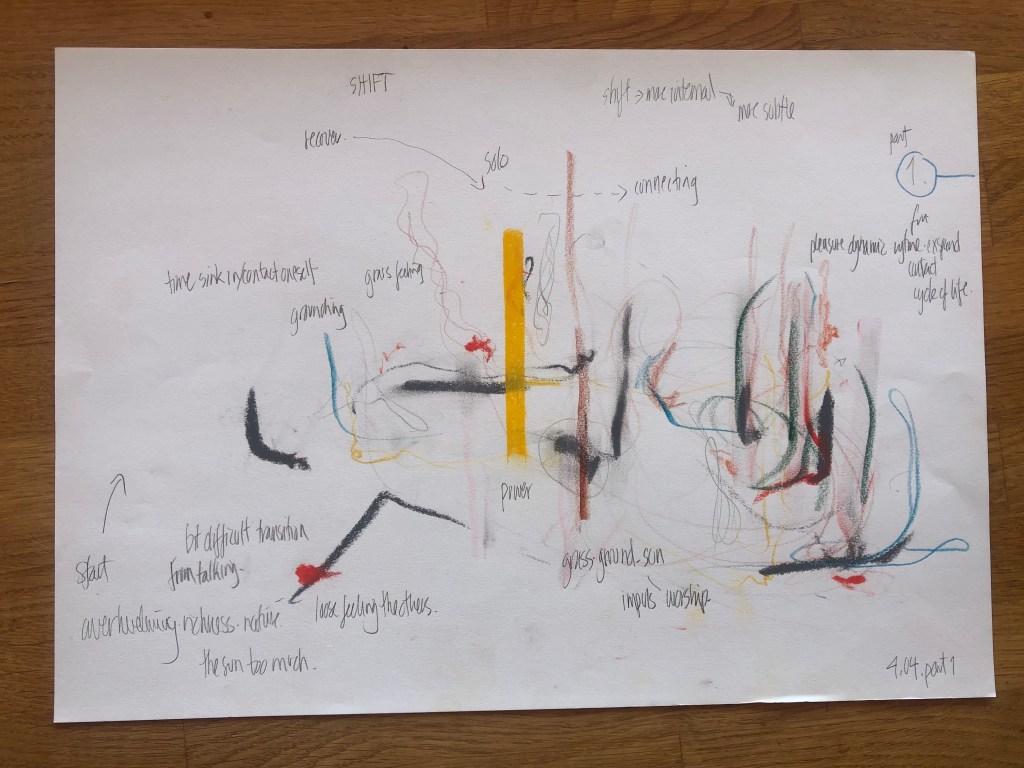

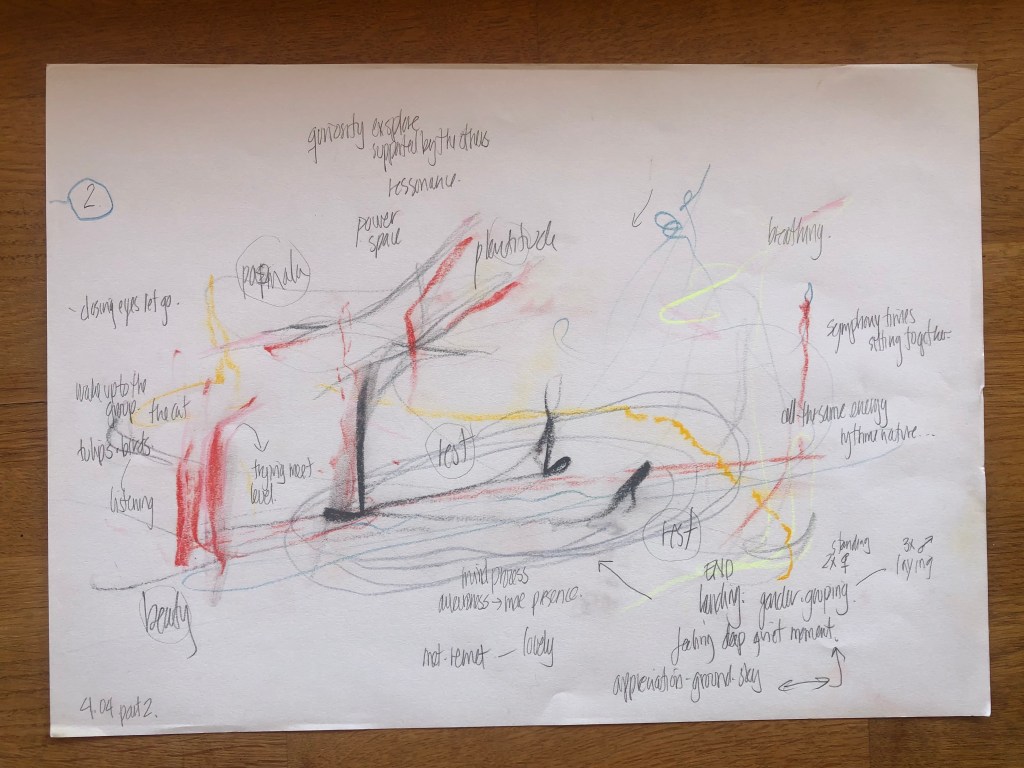

As part of this inquiry, Ninni Sødahl contributed as a “field listener,” using live drawing to capture subtle shifts in posture, proximity, and spatial relationships within the group. Her sketches offered a third feedback modality—alongside verbal reflection and embodied sensing—by making visible the evolving patterns of relational attention. These visual records captured recurring geometric patterns in group movement, such as participants aligning in the same direction, dispersing asymmetrically, or forming temporary structures through coordinated folding and unfolding. Moments of lying down in parallel, described metaphorically as “floating logs,” illustrated how individual bodies negotiated space collectively, generating visual compositions that reflected underlying energetic and attentional states. Sødahl’s work highlights drawing as a form of somatic inquiry, capable of revealing the hidden architectures of collective presence.

This body of work contributes to a growing field of inquiry into relational infrastructures for collective sense-making in both scientific and collaborative contexts. It highlights the value of integrating multiple ways of knowing—subjective, intersubjective, objective, and aesthetic—to better understand the dynamics of complex social systems. In particular, it points to the potential of awareness-based methods, often situated outside formal epistemological frameworks, to offer actionable insights into group dynamics, collective intelligence, and adaptive capacity at the team level.

Conventional approaches in organizational science and network analysis often model individuals as rational and relationally discrete, viewed from a third-person, external perspective. In contrast, the practices we engaged in during the residency offer a view from within the system—closer to inhabiting a hypergraph of co-experienced events, where groups operate as dynamic fields of coherence, tension, and transformation. Here, meaning and emergence are not just outcomes to be measured, but phenomena continuously enacted through shared attention, bodily presence, and affective resonance.

This shift in perspective is not only theoretical; it has direct implications for how we design and support containers for group processes. It suggests that team and organizational effectiveness depends not only on structure, tasks, or roles, but on how a group maintains a coherent relational field—how it navigates tensions, sustains connection, and collectively adapts. In this view, group health becomes a vital dimension of social health—less about individual well-being alone, and more about the collective’s ability to stay responsive, attuned, and generative over time.

The final day of the residency took place at the Learning Planet Institute in Paris, where we discussed with students designing inclusive experiences for youth with disabilities in cultural festivals. This encounter grounded our inquiry in real-world application, creating a bridge between exploratory pedagogy and concrete social design. It highlighted the importance of prototyping with communities, not simply for them—a principle at the heart of inclusive and participatory approaches to change.

In conclusion, the residency offered more than an alternative curriculum. It functioned as a transdisciplinary inquiry into how knowledge is formed and held—across bodies, relationships, and systems. It proposed new research methods for observing and co-shaping complex social dynamics, and offered practical tools for learning and collaboration. By integrating multiple modes of knowing, it pointed toward a science and pedagogy that are both rigorous and relational—capable of engaging with the complexity of lived experience without reducing it.

The Crafting Pedagogies of Togetherness residency was conceptualized and delivered by Studio Atelierista and co-funded by Erasmus+. The Paris 2025 Studio Atelierista team included: Ricardo Dutra, Arawana Hayashi, Anne-Sophie Dubanton, Agathe Peltereau-Villeneuve, Candice Marro, and Marina Seghetti. Follow and support their work: